Proclamation of Commonwealth.

- It shall be lawful for the Queen, with the advice of the Privy Council, to declare by Proclamation that, on and after a day therein appointed, not being later than one year after the passing of this Act, the people of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Tasmania, and also, if Her Majesty is satisfied that the people of Western Australia have agreed thereto, of Western Australia, shall be united in a Federal Commonwealth under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia. But the Queen may, at any time after the Proclamation, appoint a Governor-General for the Commonwealth.

The Annotated Constitution written by Quick and Garran make the following comments; Page 328, (relevant part only).

HISTORICAL NOTE.- Clause 3 of the Commonwealth Bill of 1891 (UK Parliament) (which became the Constitution Act 1900) was as follows:-

“It shall be lawful for the Queen, by and with the advice of Her Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council, to declare by Proclamation that, on and after a day therein appointed, not being later than six months after the passing of this Act, the colonies shall be united in one Federal Commonwealth under the Constitution hereby established, and under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia; and on and after that day the said colonies shall be united in one Federal Commonwealth under that name.”

At the Adelaide Session (Constitutional Convention Debates), the clause was introduced in the same form, except that it was provided that the colonies “shall be united in a Federal Constitution under the name of the Commonwealth of Australia, and on and after that day the Commonwealth shall be established under that name.”

The Queen may, at any time after the making of the proclamation, appoint a Governor-General for the Commonwealth.

The words “of the Commonwealth Bill” point out the influence that Australia had in the creation of the Constitution Act.

The Annotated Constitution written by Quick and Garran make the following comments; Page 328, (relevant part only).

This was agreed to. Drafting amendments were made after the fourth report. In the Imperial Parliament, the names of the federating colonies were filled in; with the provision for including Western Australia in the Proclamation if the Queen were satisfied that the people of Western Australia had agreed to the Constitution.”

Privy Council.

This body was originally one of the most important councils of the Crown. It acquired the last-named designation during the reign of Henry VI. (1422–1461). It was a council of confidential advisers, who were in constant attendance upon the king and assisted him in the decision of all questions of public policy and in the administration of the business of the kingdom. It consisted of nobles and other eminent persons in whom the king had confidence.

Lord Hale referring to the fact that the members of that council, being peers, in consultation with the king, they prepared the business. It was foreshadowed in the reign of Henry III, and assumed a definite organization during the long period covered by the successive reigns of the three Edwards. It was one of the three groups into which the Great Council was originally divided and which afterwards became fused into the House of Lords.

These groups were—

- The Lords Spiritual;

- the Lords Temporal; and

- the official and bureaucratic element immediately associated with the king in the government of the realm.

The Cabinet has been defined as the political committee of the Privy Council,

especially organized for the purpose of advising the Crown, directing all public departments, and deciding all important questions of administration, subject only to the approval of the House of Commons.

In Colonial causes the Privy Council had, from time immemorial, both original and appellate (Appeal) jurisdiction.

And to the same supreme tribunal there is an appeal in the last resort from the sentence of every court of justice throughout the colonies and dependencies of the realm. Practically, however, all the judicial authority of the Privy Council is now exercised by a committee of privy councillors, called the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, who hear the allegations and proofs, and make their report to Her Majesty in council, by whom the judgment is finally given.

The statutory jurisdiction of the Privy Council was first regulated in 1833 by the Act of William IV, passed for the better administration of justice in the judicial branch of the Council.

Under that law the Judicial Committee of the Council was definitely constituted.

The Erection of the Commonwealth.

Three distinct stages in the erection of the Commonwealth are contemplated by this clause:—

- The passing of the Imperial Act,

- the issue of the Queen’s proclamation appointing a day within one year after the passing of the Act,

- the day when the people of the concurring colonies are united. These events and successive stages are not chronologically narrated in the clause. It will be conducive to clearness to consider them in the order of time in which they occur.

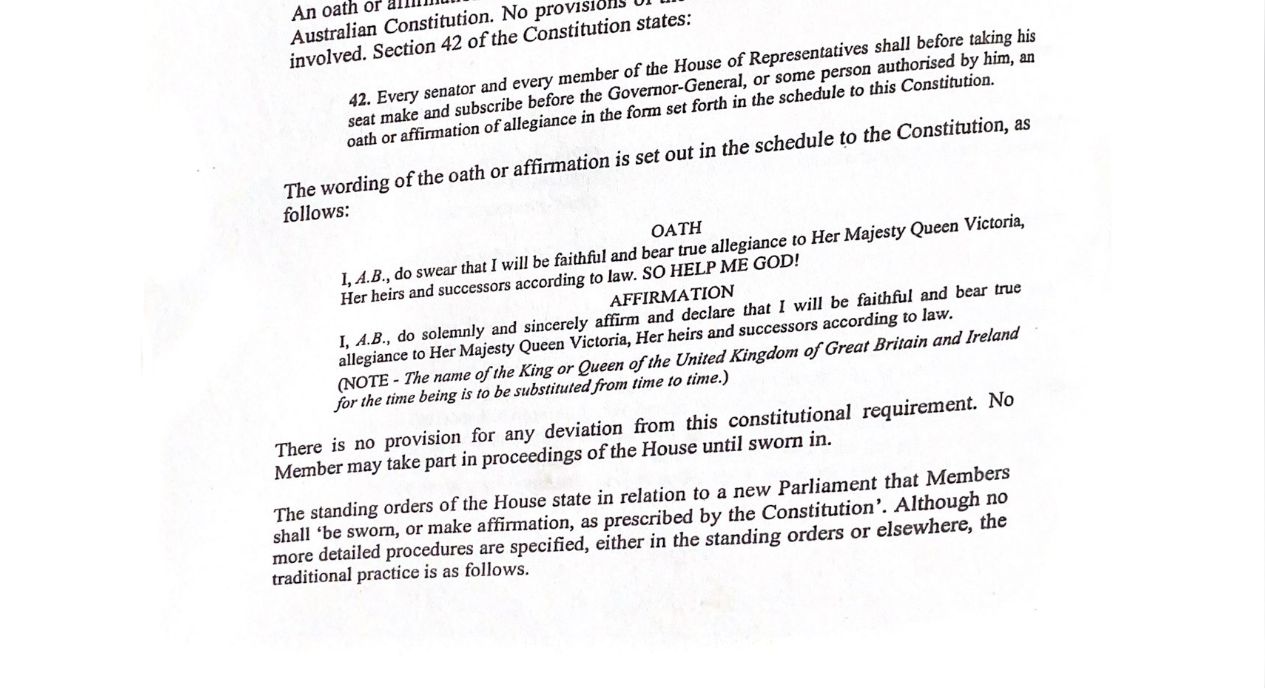

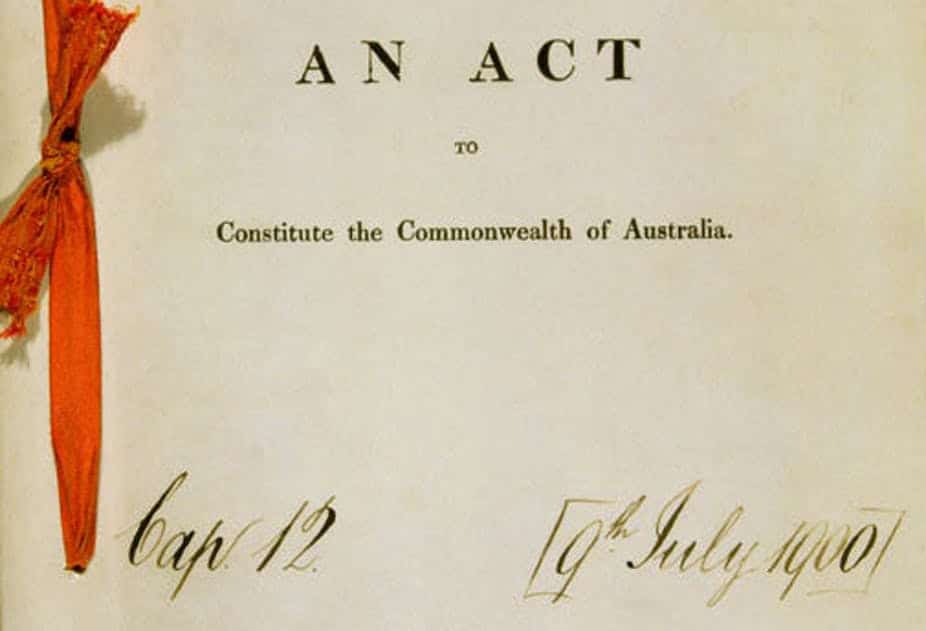

The Passing of this Act.

Before the Act, every Act in which no particular time of commencement was specified, operated and took effect from the first day of that session of Parliament in which it was passed. An Act which was to take effect from and after the passing of the Act operated by legal relation from the first day of the session. But now, where the commencement of an Act is not provided for in the Act, the date endorsed on the Act, stating when it has passed and received the Royal assent, is the date of its commencement. The Royal assent may be given during the course of the session, in which the two Houses of Parliament concur in it, or at the end of the session. The practice is to endorse on the first page of the Act, immediately after the introductory title, the date of the Royal assent.The Royal assent to an Imperial Act is given by the Queen in person or by commission; if by commission it is only given to such bills as may be specified in the schedule thereto.This Act received the Royal assent on 9th July, 1900, which day is therefore the date of “the passing of this Act.” But, although that date marks the commencement of the Act, the Commonwealth is not established, nor does the Constitution take effect, until the Queen has made a proclamation under the Act and the day fixed by that proclamation for the establishment of the Commonwealth has arrived. The only immediate consequences of the passing of the Act were:

- That the Queen in Council was empowered to issue a proclamation appointing a day, not later than one year after the passing of the Act for the establishment of the Commonwealth “Proclamation”), and

- that the Parliaments of the several colonies might proceed to pass preliminary electoral laws and to make arrangements for the election of the first Federal Parliament.

Proclamation.

A royal proclamation is a formal announcement of an executive Act; such as a summons to the dissolution of Parliament; a declaration of peace or war; a warning to the people to keep the law, or a notification of enforcement of the provisions of a statute, the operation of which is left to the discretion of the Queen in Council. The object of a royal proclamation is only to make known the existing law or declare its enforcement; it can neither make, nor unmake the law. A proclamation is a resolution of the Queen in Council, which, as we have already seen, means the Cabinet.

The proclamation referred to in this clause is one which it is in the discretion of the Queen, acting on constitutional advice, to issue subject only to the condition that the date fixed therein must be not later than one year after the passing of the Act.

A Day therein Appointed.

Where an Imperial Act of Parliament is expressed to come into operation on a particular day, it is construed as coming into operation immediately on the expiration of the previous day. Thus if the day appointed is the 1st January, the day begins at midnight, marking the end of 31st December. This principle will apply to the day appointed in the Queen’s proclamation. An expression of time in an Imperial Act, in the case of Great Britain, means Greenwich Mean Time. Definition of Time Act 1880, Interpretation Act 1889. On the day appointed by the proclamation, the following events are declared to happen,

- The people of the colonies are united.

- The Commonwealth is established.

- The Constitution takes effect.

- The electoral and other procedure laws passed by the Parliaments of the federating colonies between “the passing of the Act” and “the day appointed” come into operation.

The People shall be United.

The formative words in this clause are more forcible, striking, and significant than those of the corresponding parts of the Constitutions of the United States and of Canada; they indicate the fundamental principle of the whole plan of government, which is neither a loose confederacy nor a complete unification, but a union of the people considered as citizens of various communities whose individuality remains unimpaired, except to the extent to which they make transfers to the Commonwealth. In the body of the Constitution it is nowhere stated that the people of the States are or shall be united.

The individual human units, the vital forces, the population of the provinces, are not even remotely alluded to.

The haziness of one and the deficiency of the other Constitution have not been allowed to damage the design of the Constitution of the Commonwealth. The union of the people of the colonies is doubly asserted and assured; first in the preamble, where it is recited that “the people have agreed to unite,” and secondly in this clause, in which it is forcefully stated with mandatory force that on the day appointed they “shall be united.

Western Australia.

The condition necessary for the establishment of Western Australia as an Original State that the Queen should be “satisfied that the people of Western Australia have agreed thereto” was fulfilled by the affirmative vote in that colony on the Constitution, followed by addresses to the Queen passed by both Houses of the West Australian Parliament.

In a Federal Commonwealth.

The word “federal” occurs fifteen times in the Act, exclusive of references to the Federal Council of Australasia Act, 1885:

- Federal Commonwealth, Preamble and Clause 3.

- Federal Parliament, sec. 1.

- Federal Executive Council, secs. 62, 63, 64.

- Federal Supreme Court, sec. 71.

- Federal Courts, sec. 71.

- Federal Court, secs. 73 ii.; 77 i. and ii.

- Federal Jurisdiction, secs. 71, 73 ii., 77 iii., and 79.

The Federal idea, therefore, encompasses and largely dominates the structure of the newly-created community, its parliamentary executive and judiciary departments.

“Federal” generally means “having the attributes of a Federation.” By usage, however, the term Federal has acquired several distinct and separate meanings, and is capable of as many different applications. In this Act, for example, the term Federal is used first in the preamble, and next in clause 3, considered as a political community or state; in various sections of the Constitution it is employed as descriptive of the organs of the central government. This use, in an Act of Parliament, of one term in reference to two conceptions so entirely different as state and government, is illustrative of the evolution of ideas associated with Federalism. In the history of Federation the word seems to have passed through several distinct stages or phases, each characterized by a peculiar use and meaning.

These meanings may be here roughly generalized as a preliminary to a separate analysis:

- As descriptive of a union of States, linked together in one political system.

- As descriptive of a dual system of government, central and provincial.

As descriptive of the central governing organs in such a dual system of government.

The first, and oldest, of these meanings directs attention definitely to the preservation of the identity of the States; the second asserts that the duality is a matter of government, not of sovereignty; whilst the third asserts nothing, but is merely a convenient form of terminology.

A Union of States.

The primary and fundamental meaning of a federation is its capacity and intention to link together a number of co-equal societies or States, so as to form one common political system and to regulate and co-ordinate their relations to one another; in other words a Federation is a union of States.

A Dual System of Government.

In recent years it has been argued that the word “federal” is inappropriately and roughly used when applied to a State or community; that there is no such thing as a federal State; that if there is a State at all it must be a national State; that any political union short of the principal attribute of statehood and nationhood, sovereignty,

Central Government of a Dual System.

The term federal” is often used as descriptive of the organs of the central and general government, such as the Federal Parliament, the Federal Executive, and the Federal Supreme Court.

Federal Structure of the Commonwealth.

The Commonwealth as a political society has been created by the union of the States and the people thereof. That the States are united is proved by the words in clause 6, which provide that the States are “parts of the Commonwealth;” that they are welded into the very structure and essence of the Commonwealth; that they are inseparable from it and as enduring and indestructible as the Commonwealth itself; forming the support of the entire constitutional fabric.

Covering Clause 6.

Definitions.

“The Commonwealth” shall mean the Commonwealth of Australia as established under this Act.

“The States” shall mean such of the colonies of New South Wales, New Zealand, Queensland, Tasmania, Victoria, Western Australia, and South Australia, including the Northern Territory of South Australia, as for the time being are parts of the Commonwealth, and such colonies or territories as may be admitted into or established by the Commonwealth as States; and each of such parts of the Commonwealth shall be called “a State.” Original States” shall mean such States as are parts of the Commonwealth at its establishment.

“The Commonwealth, however, is not constituted merely by a union of States; it is something more than that; it is also a union of people.”

State Rights—Federal.

The sections which guarantee equal representation in the Senate and a minimum representation in the House of Representatives; which enable the Governors of States to issue writs for the election of Senators and to certify their election to the Governor-General; which require the Governor of a State concerned to be notified of vacancies in the Senate; State Constitutions except so far as they are inconsistent with the Constitution of the Commonwealth and its laws; which continue the power of State Parliaments except to the extent to which it has been withdrawn from them or vested in the Commonwealth; which continue.

State laws in force until provisions inconsistent therewith are legally made by the Federal Parliament; which preserve to each State the right to have direct communication with the Queen on all State questions; are examples of State rights secured by provisions of a Federal character.

The Constitution is National so far as it makes the laws of the Commonwealth binding on the people, Courts and Judges of every State; so far as the High Court has jurisdiction (sec. 73) to hear and determine appeals from State courts on questions of State laws; so far as the High Court has original jurisdiction (sec. 75) in certain classes of matters; so far as the Parliament has power to make laws (sec. 76) conferring original jurisdiction on the High Court in certain other classes of matters; so far as the Federal Parliament has power (sec. 77) to nationalize (take over) State courts by investing them with Federal jurisdiction.

Federalism in the Judicial System.

The Constitution is federal so far as it preserves the operation of State laws, not inconsistent with Commonwealth laws; so far as the State courts have exclusively original and primary jurisdiction to entertain matters in which State laws are involved; so far as it provides that the trial, on indictment, of an offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be held in the State where the offence was committed (sec. 80).

Powers of the Federal Parliament.

It is in the distribution of legislative powers between the Federal Parliament and the State Parliaments that the fundamentally federal basis of the Constitution is most apparent; yet even here there is a distinct predominance of the national element. Looking down the sub-sections of sec. 51, we find that in many of them the principle of duality is expressly recognized, and the exclusive domestic jurisdiction of the States expressly reserved. For instance, the trade and commerce power is confined to inter-State and foreign trade and commerce, and it is hedged in (Chap. IV.) with a number of small restrictions to prevent injustice or discrimination as between States. The federal power of imposing taxation and granting bounties is similarly hedged about with conditions for the protection of the States. In sub-sec. x., the power over fisheries is confined to waters beyond territorial limits—the territorial rights of the States being thus reserved. In sub-secs. xiii. and xiv., the powers as to Banking and Insurance also contain a reservation of State rights.

In sub-sec. xxxv., power to deal with conciliation and arbitration is only given in the case of inter-State industrial disputes, and so on.

In all these cases, the duality of interest is recognized in the very gift of the power to the Federal Parliament, and the distribution of power is thus essentially federal. But in most of the subsections this nice analysis is not found.

Powers of the Federal Executive.

In other matters the original jurisdiction of the State courts is exclusive. The appellate jurisdiction of the High Court, on the other hand, is completely national and is in fact the most national element in the whole Constitution. It extends, subject only to partial limitation by the Federal Parliament to cases of every description decided by the Supreme Courts of the States, whether of federal concern or not. The High Court is, in fact, not a federal court of appeal, but a national court of appeal.

Composite Character of the Constitution.

It thus appears that even according to the more modern meaning of the word “federal” which recognizes the national as well as the provincial elements of federalism, the Constitution may be described as partly federal and partly national. That is to say, it contains not only those national elements which relate to a pure Federation, but also some further national elements which relate to a unification. This is especially the case with regard to the wide extent of some of its legislative powers, and with regard to the unlimited appellate jurisdiction of the High Court.

Credit: (CLRA) Community Law Resource Association

Authorised by Ian Nelson for the Great Australian Party, 65 Cardinal Cct, Caboolture, 4510